Resettling an entire ethnic group in another country is a monumental task fraught with legal, political, and logistical complications.

But that’s what Kyrgyz President Sadyr Japarov wants to do with 1,500 nomadic Pamir Kyrgyz who eke out a pastoral existence in the most remote corner of northeast Afghanistan.

A century of isolation in the panhandle of Badakhshan Province has insulated the Pamir Kyrgyz from the decades of war that have ravaged Afghanistan.

But life there can be as harsh as the winter winds.

With a diet devoid of fruits and vegetables, and with only sporadic medical care from traveling doctors, the Pamir Kyrgyz have one of the world’s highest infant mortality rates and shortest life expectancies.

Last winter was particularly brutal.

Even with helicopters airlifting emergency medical and food supplies, scores of Pamir Kyrgyz nomads died from illness and malnutrition.

Japarov is vowing to build new houses for all of them within the mountainous Chong-Alay district of Kyrgyzstan’s southwestern Osh region.

“The hardships of the Pamir Kyrgyz have been constantly disturbing my thoughts for a long time,” Japarov said on April 4. "I have had the desire for them to be resettled in their historical homeland for a long time and now I mean to realize these intentions.”

“I will do this as soon as possible,” Japarov said. “This issue will be under my control. We do have financial resources and a plan about how and where they will be relocated. We will create good conditions for them.”

Implementing the plan will require at least tacit approval and cooperation from Afghanistan’s government.

It also will require the willingness of the Pamir Kyrgyz themselves to leave the two valleys on “the roof of the world” that they call home -- the Big Pamir and the Little Pamir.

Just days before Japarov announced his initiative, Afghan Foreign Minister Mohammad Hanif Atmar met in Kyrgyzstan with Pamir Kyrgyz families who’ve resettled there since 2017.

They said it’s important to be granted Kyrgyz citizenship as soon as possible -- a legal status allowing them to travel abroad as well as clearing bureaucratic hurdles for state pensions and social benefits.

They’ve seen progress on that issue.

On April 28, Bishkek granted Kyrgyz citizenship to 44 former Pamir residents who’ve resettled in the village of Sary-Mogol in the Alay district of the Osh region.

But others say they still have concerns about the provision of land plots and the transformation of the land.

The Kyrgyz government has already paid for the transit of 33 resettled Pamir Kyrgyz and provided homes for them.

Afghan officials have declined to comment publicly on the resettlement proposal.

Afghan government sources privately tell RFE/RL it is a sensitive issue that is “under assessment.”

History On The World's Roof

Scalloped out by a glacier in mountains that tower more than 7,000 meters above sea level, the Big Pamir and Little Pamir valleys lie along the route that Venetian merchant-traveler Marco Polo took on his journey to China in the late 13th century.

Central Asian historians say the Pamir valleys were a place of seasonal migration for nomadic Kyrgyz herders at least as far back as the 1570s.

They pastured livestock there during the second half of the 19th century when the mountain valleys were on the fringe of the expanding Imperial Russian Empire’s Turkestan region.

It was the geopolitics of the late 19th and early 20th centuries that boxed in the Little Pamir and part of the Big Pamir between the borders of what is now Tajikistan, China, Pakistan, and Pakistani-administered Kashmir.

In an attempt to bring their Great Game confrontations to an end in the 1890s, cartographers from tsarist Russia and British Colonial India created the panhandle of northeast Afghanistan, known as the Wakhan Corridor, as a buffer zone between their empires.

Then, following the Central Asian revolt of 1916 in Russia’s Turkestan region, Kyrgyz refugees fled into western China and the Wakhan Corridor to escape a ruthless crackdown by Russian forces.

Today’s Pamir Kyrgyz in the Wakhan Corridor are descendants of the nomadic herders who sought safety there in 1916.

Ted Callahan, an anthropologist who lived with the Pamir Kyrgyz for some 15 months between 2006 and 2010, says the development of the Soviet Union after Russia’s 1917 Bolshevik Revolution changed the lives of the nomadic herders immensely.

“Prior to the establishment of a hard border, they had freely crossed the Panj River going from what’s now Tajikistan into Afghanistan,” Callahan explains. “But Soviet troops were sent to garrison that border and enforce border controls that divided the Big Pamir.”

“The Pamir Kyrgyz found it much more difficult to follow their nomadic seasonal patterns in which they’d often go up to the Pamirs for the summer and spend the winter in lower lying areas -- whether that was in China or [Imperial] Russia,” Callahan told RFE/RL.

“The geopolitical forces around them hardened the borders,” Callahan says. “They found that Afghanistan offered them a safe haven. So they adapted their pastoral nomadic structure to a much more constrained environment, living in the Pamir Mountains of Afghanistan full time.”

Afghanistan’s Saur Revolution of 1978, a Soviet-backed coup d’etat against the rule of Afghan President Mohammad Daud Khan, brought another change that divided the Pamir Kyrgyz.

Haji Rakhmankul Khan, the strongman leader of the Pamir Kyrgyz clans, organized an exodus of some 1,500 herdsmen into Pakistan shortly before the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

He left only a few disgruntled families behind in his stronghold, the Little Pamir, and about 500 herders in the Big Pamir.

“They saw the mobilization of Soviet forces across the border of Afghanistan,” Callahan explains. “By this point, there was a lot of bad blood between the Pamir Kyrgyz and the Soviets -- a long history of cross-border raiding, punitive expeditions against the Kyrgyz in the Pamir. They feared that if the Soviets came in they would be persecuted.”

Callahan says the exodus became a great opportunity for most of those who stayed behind in the Big Pamir because “they were freed from Haji Rakhmankul’s autocratic leadership.”

“They had a lot of pasture open up,” Callahan says. “Relatively few actually moved into the Little Pamir because there wasn’t enough manpower there for their labor-intensive lifestyle.”

“What also happened is that the others left a lot of their livestock behind, thinking their move to Pakistan was going to be a temporary relocation and they would potentially come back,” he said.

But life as refugees in a relatively low-altitude part of Pakistan proved to be difficult for them. Before long, more than 100 died in the warmer climate.

“They sent a scouting mission back into Afghanistan after the Soviets did invade, and it turned out that things weren’t so bad there,” Callahan explains. “Meanwhile, there were fissures growing within the Kyrgyz community in Pakistan.”

“Some who were still close to Haji Rakhmankul were willing to stay with him -- his kinfolk and others,” Callahan says.

In 1982, Ankara agreed to host Rakhmankul Khan and 1,200 Pamir Kyrgyz refugees still with him in Pakistan. A United Nations airlift delivered them to a new settlement near Van Lake in mostly Kurdish southeastern Turkey.

Today, that community in the village of Uluu Pamir, Turkey, is more than 2,500 strong and is seen as an example of a successful resettlement.

Meanwhile, about 50 families who were unhappy with Rakhmankul Khan’s leadership refused to go with him to Turkey. They packed up their yurts in Pakistan and returned to Afghanistan.

Callahan, whose research has focused on the political power structure of the Pamir Kyrgyz clans, says there was a much bigger fracturing of leadership when he lived with them in Afghanistan.

“Haji Rakhmankul Khan was the last of their traditional khans,” he says. “He had authority, but he also had the ability to compel -- meaning he could rule by force rather than by persuasion.”

Callahan says the livestock holdings were much more evenly disbursed when those who split with Rakhmankul returned to Afghanistan.

“You didn’t have a khan who controlled all the livestock and could withhold it from people,” he explains. “There weren’t any extremely rich guys who were interested in political power. So there hasn’t been the development of a highly vertical leadership structure there since then.”

At one point, three different clan leaders claimed to be the rightful khan.

“All of the subsequent khans have had to work through consensus,” he says. “They haven’t had power in the sense of being able to force anybody to do anything.”

That gives members of today’s Pamir Kyrgyz community in Afghanistan more independence to decide for themselves whether or not to accept Japarov’s offer to resettle in Kyrgyzstan.

Nomadic Life vs. Modern World

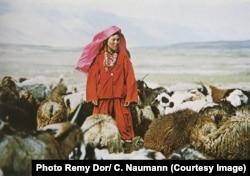

The rhythm of life for the nomadic Kyrgyz in Afghanistan is still the sun and seasons, not manmade clocks.

During the summer, they live in yurts on the southern side of the Big Pamir and Little Pamir valleys -- the shady side -- where they tend their sheep, goats, and yaks.

In the winter, they “up stick” their yurts and move to mudbrick huts they’ve built on the north side of the Little Pamir valley floor and near the Panj River in the Big Pamir.

There is more sun there, which means the snow melts faster. And the mudbrick shelters give better protection from the winter winds that scour the valley’s gently rising sides.

Tobias Marschall, an anthropologist who spent about 11 months living with the Pamir Kyrgyz nomads between 2015 and 2019, says clan elders have mixed views about whether they should stay or go.

“I know from a lot of families that a lot of people don’t want to leave the Afghan Pamir,” Marschall tells RFE/RL. “They resist those plans to be relocated in Kyrgyzstan and don’t want to be framed as people who need help. They value the lives they have in this land.”

“One of the leaders told me ‘I will be the last one to leave the Afghan Pamir,'” Marschall says. “He was expressing his opposition to the resettlement plan. There is opportunity in the relative freedom of being so remote and owning the resources there.”

“This doesn’t mean every leader wants to remain,” Marschall concludes. “It will be a mixed reaction as it was already. Some will see an opportunity to escape conditions that are binding and difficult. That will be more of the poorest elements of the community.”

Scores of young Pamir Kyrgyz in Afghanistan tell RFE/RL they welcome the idea of starting a new life in Kyrgyzstan -- suggesting it is only a few elderly clan members who may want to stay behind.

Many say the lack of access to education is the reason they want to leave. In the Pamir, most children must walk more than an hour to reach a distant schoolhouse on days when they’re not tasked with watching livestock.

Otherwise, they rely on traveling teachers who sporadically visit their yurts.

Habib ul-Rahman, a 22-year-old ethnic Kyrgyz man from the Big Pamir, completed the ninth grade in a yurt and a school house at the entrance to the valley.

He has since left the Big Pamir to try to learn English in Faizabad, the capital of Badakhshan Province.

“We are a minority isolated in the Pamirs and the government does not pay attention to us,” Rahman told RFE/RL. “We do not have access to things from the government there, so we accept resettlement 100 percent.”

“We have contact with those who’ve already gone to Kyrgyzstan,” Rahman explained. “They say they are very happy because they are provided with facilities. They’ve been given a house and land. They go to school. They study.”

“I call on the Afghan government to cooperate with our [moving] to Kyrgyzstan,” he said.

For 28-year-old Rakhmankul to complete his high-school education, he had to move to Badakhshan’s Ishkashim district after finishing ninth grade in the Big Pamir.

He is now in his first year of medical studies in the nursing department of the Badakhshan Institute of Health Sciences in Faizabad.

“We have no particular worries about going to Kyrgyzstan,” Rakhmankul told RFE/RL. “If we go there it will be enough for people not to face economic hardship and receive support until the people can study, get settled, and have houses built for them.”

“But there must be jobs for those who go there,” Rakhmankul says. “Livestock opportunities should be provided for adults who have been engaged in animal husbandry.”

“Our request to the Kyrgyz government is that if they take us, it should be near a city,” he says. “They should not put us in an isolated mountainous place like the Pamirs. The children must be able to study and be educated there.”

Leaving Afghanistan Behind

Habibulla Muhammad-uulu is a former shepherd who moved with his wife and children in 2019 from Badakhshan’s Kichi Pamir settlement to Kyrgyzstan’s Naryn region.

After working three months to obtain Afghan passports for his family, Muhammad-uulu funded their journey by selling his livestock in the Big Pamir valley -- then hiring a taxi to Kabul and taking a flight to Bishkek via Dubai.

“Kichi Pamir is a place of God. It's a good place,” Mohammad-uulu tells RFE/RL. “But it's hard to get supplies there for living. For that you must travel five days on yaks one way to Pakistan and another five days to return. It's very cold out there. Children and women die very often.”

Mohammad-uulu says it was not hard for his family to adjust to life in Kyrgyzstan.

He says there are language differences as his family uses some Dari words while most Kyrgyz use various Russian words. Still, he says they do not have difficulties understanding each other.

Mohammad-uluu says life has changed in a good way for his family.

“It is much easier to get all necessary goods here,” he says. “You don't get sick often. Even if you do, doctors will take care of you anytime. Pamir has a higher altitude. You feel as if you are heavy. You have a headache very often. Your bones, legs, and arms are aching as well.”

“In Pamir, we ate a lot of meat from sheep and ibex,” he continues. “That's what we miss here. Here we have apples, onions, and potatoes. That's what we didn't have back in Pamir. There we only had meat, rice, and bread.”

In the Big Pamir, Mohammad-uulu spent much of his time watching after his own livestock while his wife made traditional yurts.

“We used to have only yaks and sheep,” he said. “Cows cannot resist the cold climate. We only had one horse that we rode for hunting.”

Now Mohammad-uulu’s job is to look after the livestock of a Kyrgyz farmer. He also is paid about $30 a month for doing garden work at a kindergarten.

“I want my kids to build families here,” he says. “It's cheaper to pay a dowry to marry a girl here and very expensive in Pamir.”

He says the Kyrgyz government helped his family by providing their first home and checking on how they were adjusting to their new life.

But he says the main reason he wants to stay in Kyrgyzstan is because his children have easy access to education.

“My children used to read in Arabic in Pamir,” he continues. “Schools in Pamir are separate for girls and boys. Here, they all study together. They also don't study during wintertime in Pamir because it gets very cold.”

But not all of those who’ve relocated in Kyrgyzstan have been so satisfied.

Out of 50 Afghan Pamirs who arrived in Kyrgyzstan’s Naryn region in 2017, 18 went back to Afghanistan by July of 2018.

All had vowed they’d return to Kyrgyzstan, but only one has done so.

Meanwhile, several of 12 Pamir families who initially tried to resettle in the Naryn region have remained dependent on support from Bishkek because they’ve had trouble finding jobs.

Last year, the Kyrgyz government moved 10 of those families to newly built houses in the village of Sary-Mogol in the Osh region.